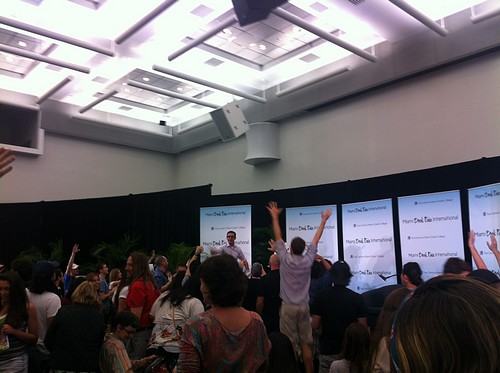

Chuck Palahniuk takes the stage in a well-tailored pink striped shirt and tan leather pants, the headline act of Saturday night at the Miami Book Fair International, and the crowd is in a Beatlemaniaesque frenzy. He quickly relates a story told to him by an oncologist he sat across the table from at a dinner party. The oncologist was on a long flight, seated next to a particularly chatty lady. She talked about this and that, and eventually got around to the subject of wine. She could no longer drink it, she said, because it caused a small burning pain in the base of her neck. “I tried beer, and it caused the same burning sensation,” she told him. “I tried liquor, and still the burning. So I figured it was just the lord telling me I shouldn’t drink anymore. But it’s the wine I miss the most.” “That’s not the lord telling you anything,” replied the doctor. “I’m an oncologist, and what you’ve got is stage-4 lymphoma. You’ll be dead by the end of the summer.” The lady was much less chatty for the rest of the flight. And when she got back home she went to see her own doctor, who called the oncologist and said, “You were right: it’s cancer and she’s got 90 days to live. But you could have been less of a dick about telling her.”

“And that,” Palahniuk tell us, “is how every good story works. It changes us. Because now, every time you have a glass of wine, you’ll be looking for that little pain in the base of your neck.” Then he proceeds to throw dozens of large inflatable kidney-shaped brains into the audience, offering prizes to the few people who inflate theirs the fastest. In case you’re like me and you’ve never heard of Palahniuk, he’s written several novels that either have been or currently are being adapted into movies, including Fight Club. They’re sometimes called “transgressive” novels, and indeed the movies leave out the most startling sections of the books. He goes on to read two stories. The first includes a scene of a woman on a bus who reaches into her jeans, pulls out a bloody tampon, and begins swinging it around at the people around her, hitting them in the head with it. Pretty gross, but nothing remotely approaching the second story — two thirds of the way through which there’s a loud crashing sound in the back of the hall. It turns out to be somebody who fainted. This is actually not surprising — I was beginnint go get queesy and light-headed myself. The fainter is helped out of the room, and a few dozen others take advantage of the opportunity to escape, mostly from the reserved VIP seats at the front of the room, all replaced immediately by motley college-aged people from one of the standby lines outside. When the commotion dies down Palahniuk says, “at this point it’s protocol to ask whether it’s okay for me to keep reading,” which is met with plenty of approving cheers. The story is Guts, and the phenomena of people passing out during its reading is apparently well documented.

Palahniuk has the headline Saturday night slot of the book fair, and he plays the rockstar role, but my favorite bit of the above — his opening story — is exactly like thousands of moments that happen over the course of the week. Most are smaller-scaled but no less profound for it.

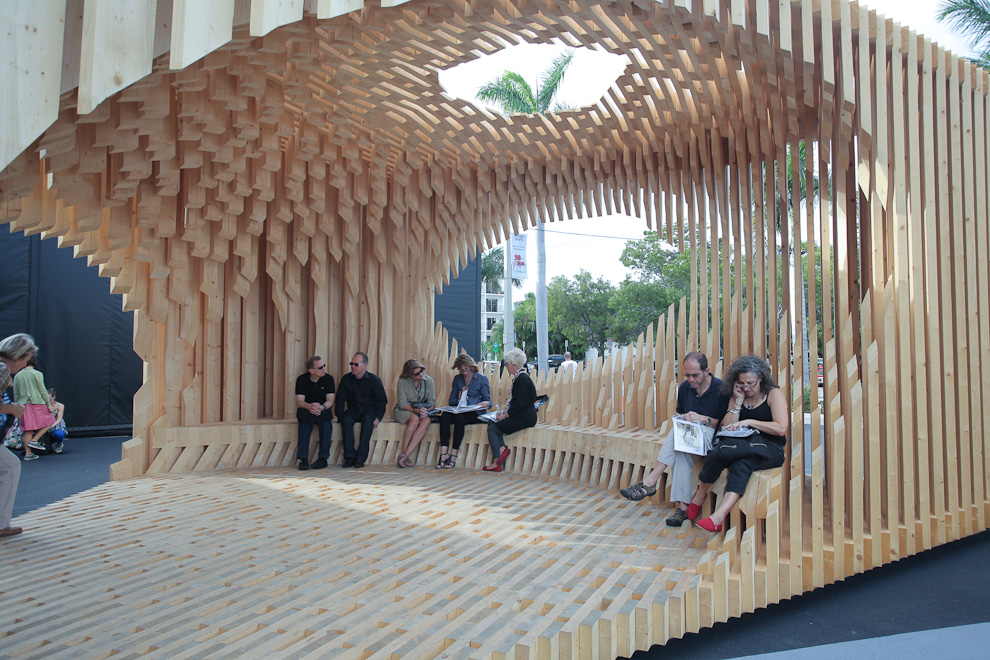

I should back up and say that in the past I’ve been a book fair skeptic. A fair about books is way closer to dancing about architecture than writing about music is, right? The process of selecting a book to read ought to be a slow and deliberate one, and having millions of books, plus crowds, is an anathema to the process, right? And the fact that the Miami Book Fair is the biggest in the nation, sprawling over six city blocks, several buildings of Miami Dade College, and a few ready-built tent pavilions, would seem to only make those matters worse. But this is my realization: It’s about moments. You can be changed by much smaller ephipanies than that a pain at the base of the neck can signal impending demise.

Earlier in the day: “In the basement the bag of fresh-picked garlic dries out, infusing the room with the pure rush of half sweat, half sex, half earth. That’s three halves, but anything pure consists of multitudes. Right, dude?” Jim Ray Daniels is reading from his entry in Tigertail’s South Florida Annual, a slim little volume with 54 pieces each limited to 305 words. Tigertail is a legendary local performing arts organization that also dabbles in poetry, and this, their ninth annual publication, is the first to branch out to prose writing. Daniels is going on in great detail about his love of garlic and his teenage sons: “They wrinkle their noses up at me like garlic is the looser in the back of class that stinks and everybody makes fun of.” And then he drops this one: “I’d trade all this garlic for a kind remark today.”

I have no idea how that reads on a computer screen to you, but in the room, for me, it was pretty striking. Sometimes, you realize how much you appreciate something only at the moment when you find yourself willing to give it up in exchange for something else.

Did I mention “sprawling”? The grid for Saturday’s events has nine time slots and twelve areas, and almost all the cells are filled with single-author or panel events. Sunday is a similar situation, and the preceding week has events every evening. There are something like 250 events.

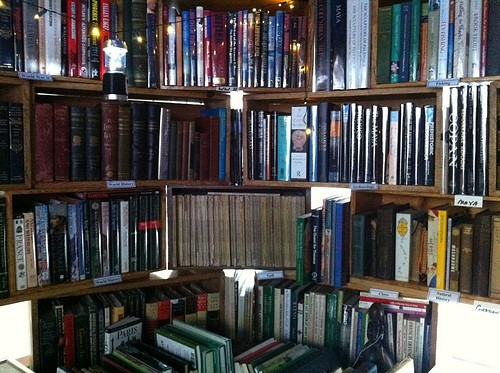

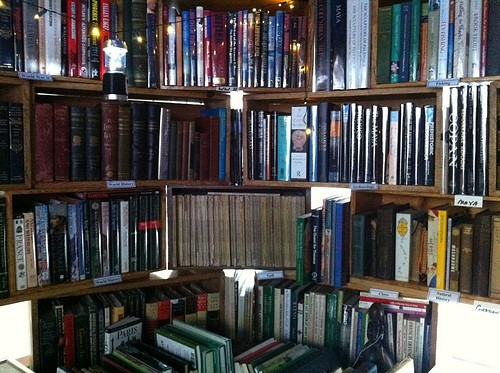

And there’s the street fair: six city blocks around the university buildings that house the author events lined with tents of booksellers. One is dedicated to antiquarian booksellers. There’s a row of author tents, mostly folks with self-published books they’re promoting. There are tents dedicated to comic books, socially aware books, children’s books, and all sorts of special interests. There are religious tents (last year I got a free Quran at one). There are several tents with the name “Los Libros Mas Pequeños del Mundo” which carry delightfully small spanish-language books on all subjects. Books & Books, Miami’s famous independent bookstore, has a sprawling tent. McSweeny’s has a tent with their exquisite books and book-like objects. And there are many many tents selling used books, each with a different level of quality, organization, and attention to pricing. (The best time to buy books is at the end of the day on Sunday. The vendors, facing the prospect of packing up their unsold books, are in the mood to make a deal. And you won’t have to carry your haul around all day.)

There’s a big children’s area with rides, story readings, face-painting, and the like. There are food tents like you’d find at any fair. There’s a large stage set up at one end of the street fair with a revolving roster of bands playing all day. And there’s the China pavilion with booksellers, calligraphy, and performances. (Every year the book fair focuses on one country and brings in vendors, authors, and performers) When I stopped by, there was a 10-piece ensemble playing traditional Chinese music, with an encore of Jingle Bells.

My favorite speaker is Colson Whitehead. A minor literary star who decided for reasons not made entirely clear to write a zombie novel, he appears on a panel with a couple of other highbrow genre novelists, except that as soon as he takes the podium to deliver his opening remarks he owns the room. African-American, Whitehead begins his remarks with the opening lines from The Jerk, and goes on to point out that while he’s been publishing books regularly, he hasn’t been invited to the Miami Book Fair since 2003. “I usually spend my Saturday afternoon at home, weeping over my regrets, so this is a welcome change,” and he launches into the story of how he became a writer, in turns holding up his hands to show his “long delicate fingers and thin feminine wrists” to explain why he wasn’t fit for a life of labor and playing the disco hit MacArthur Park from his iPad into the podium microphone. The song’s lyrics would only make sense to him decades later when rejection slips for his first novel began to come in. (And yes, there is a line-by-line explanation of this, but it alas defeated my note-taking abilities.) He explains that his family watched a lot of TV when he was growing up, and that he saw A Clockwork Orange at age 10: “Mommy, what are they doing to that lady?” “It’s a comment on society.”

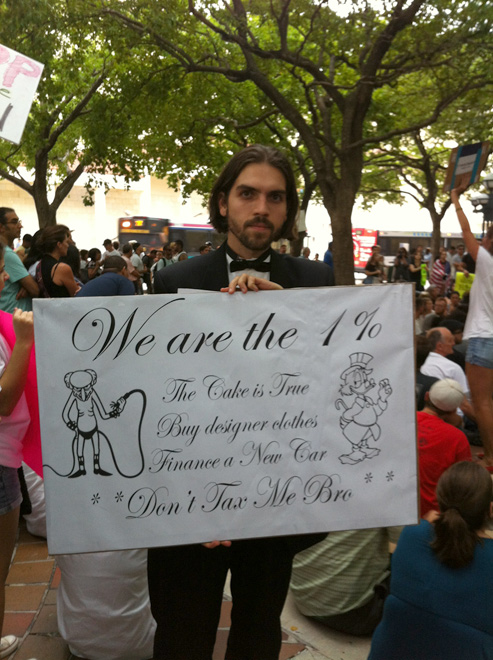

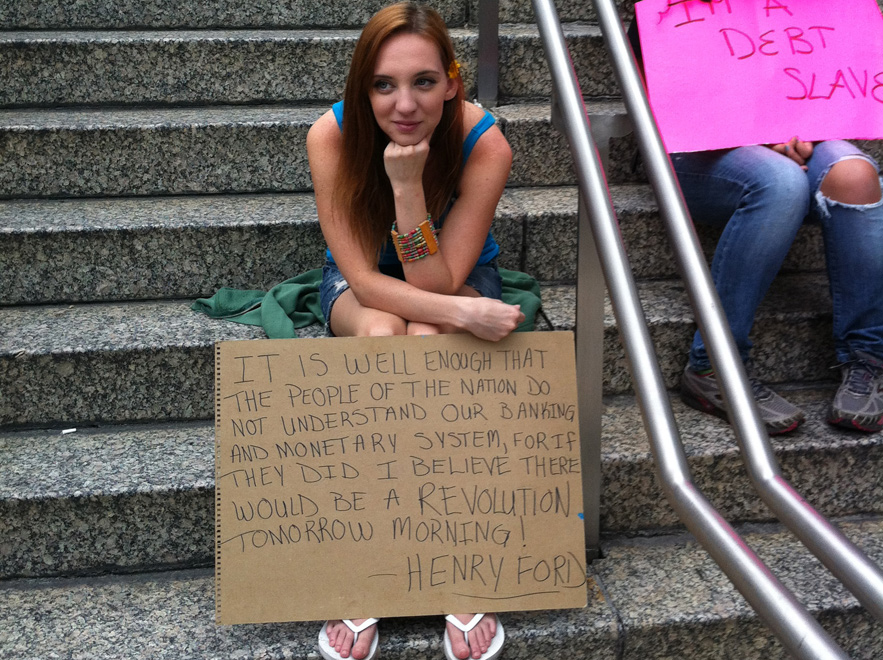

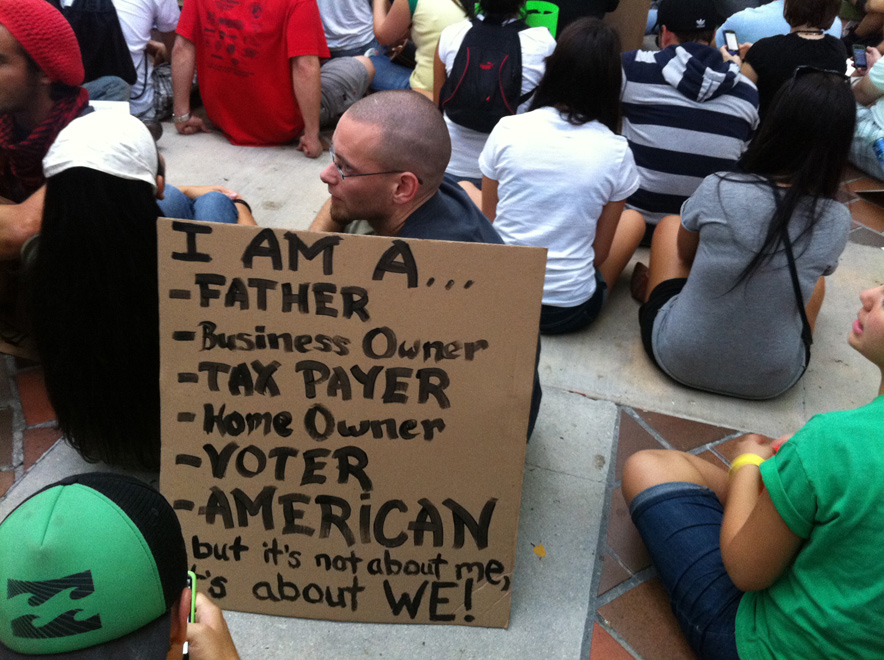

Just as funny if less charismatic is Andy Borowitz, who’s at the fair on the pretense of having edited a book of the “50 funniest American writers” and uses the opportunity essentially to deliver a stand-up monologue about the Republican primary race. “If you watch cable news because you want to be better informed,” he quips, “that’s like going to the Olive Garden because you want to live in Italy.” Much better political jokes come from the cartoon artist Mr. Fish, who’s razor sharp barbs spare nobody (he received death threats for his criticism of President Obama early in his administration), but who is touchingly accommodating of the Occupy Wall Street’s movement’s lack of an expressed agenda: “It’s like asking a group of starving people to agree on a menu before you’ll listen to them.”

I’m still not sure why the Miami Book Fair charges admission. The high-profile author events with limited seating, yes. But the street fair, a hundred or so tents of books large and small, famous and obscure, expensive and nearly free (or completely free, as in the case of a Quran I received last year) — why charge? In any case, it’s been so for years, and it doesn’t keep the visitors at bay. By noon the street fair is a throng, and the more popular author events fill Miami-Dade College’s Chapman conference hall with long standby lines to spare.

Even with Michael Moore closing out the last day of the Book Fair, this year’s line-up couldn’t match 2010’s star-studed roster, which included Jonathan Franzen, John Waters, and Patti Smith. But it turns out to be even more wonderful that way. The revelatory moments the book fair always brings are that much more special when they’re unexpected.

A few years ago I was on a panel of Miami arts writers at Locust Projects with Anne Tschida, Omar Sommereyns, and a few others (my qualifications seemed a bit sketchy, but it was certainly a good discussion). Probably the biggest takeaway from the (sizable!) audience was that they were clamoring for more local arts coverage and, in particular, criticism.

A few years ago I was on a panel of Miami arts writers at Locust Projects with Anne Tschida, Omar Sommereyns, and a few others (my qualifications seemed a bit sketchy, but it was certainly a good discussion). Probably the biggest takeaway from the (sizable!) audience was that they were clamoring for more local arts coverage and, in particular, criticism.