Ken Rockwell’s How to Win at eBay article should be worth a read.

Category: Technology

What’s up with text messages?

I’ve been griping about this for years: it costs cell-phone carriers effectively nothing to send text messages, yet they’re charging 10 or 20 cents a piece. Consider the size of an mp3 file vs. a text file: my This American Life downloads (which are of course efficient, low-quality files) are 27,700 kilobyte files, which comes to 470 kilobytes — or 470,000 bytes — per minute. How many bytes is a 160 character text message? I actually had to work this out, but you’d be correct to guess that in text messaging, one character still = one byte, so it’s 160 bytes.

I’ve been griping about this for years: it costs cell-phone carriers effectively nothing to send text messages, yet they’re charging 10 or 20 cents a piece. Consider the size of an mp3 file vs. a text file: my This American Life downloads (which are of course efficient, low-quality files) are 27,700 kilobyte files, which comes to 470 kilobytes — or 470,000 bytes — per minute. How many bytes is a 160 character text message? I actually had to work this out, but you’d be correct to guess that in text messaging, one character still = one byte, so it’s 160 bytes.

I.e., one minute of audio costs phone companies several thousand times as much to transmit as a text message. Calling plans are of course totally arcane, but an average between pay as you go and the less expensive monthly plans seems to be about ten cents per minute of calling. So, they’re charging twice as much for the text message while it’s costing them 1/1,000th as much to send (this is actually a conservative estimate which assumes that the phone call uses a quarter of the bandwidth as the This American Life mp3). In other words, Highway 2B Robberiez.

So the obvious solution is to not send text messages? Well, not really. If we knew they cost 20 cents before, they’re obviously worth it to us to send. This is what happens in Europe: Nobody has a prepaid plan: you pay for the minutes you actually use. (In an added twist, only the person initiating the call is charged.) Text messages are charged some trivial amount, which makes a round of texts much cheaper then a short conversation.

So, I’m not sure we want a world where minutes on the phone are expensive and text messages are cheap. I guess what I’m saying is, look at your cell phone bill. If it makes sense for you to switch to a cheaper plan, do it. If you’re off-contract, consider a pre-paid plan. And if you’re sending and receiving an average of 5 text messages a day, consider whether that $30 per month is really worth it to you.

Image: IamSAM

Fuck you, Picasa

Like a complete n00b, I use Picasa to manage my computer photo archive. In conjunction with a couple of lightweight photo viewers and Photoshop, I can do whatever I need. It easily imports, does light photo modification, and exports in conveniently resized batches.

It’s got it’s share of flaws too, though. The color balance is just useless for removing anything but the faintest of color casts, there’s no way to darken midtones (fill light will lighten midtones, but the slider only moves in one direction?!), and it’s impossible to apply sharpening after an export/resize, which is the only time sharpening makes any sense (so everything going to the web needs to be run through a photoshop unsharp mask first).

But it was all stuff I could deal with, until yesterday. See, it turns out that the import option “Safe delete: only pictures that are copied will be deleted from the source media,” really means “UNLESS ANYTHING WHATSOEVER GOES WRONG, THEN I DELETE YOUR PHOTOS PERMANENTLY.”

What happened apparently was that the destination drive was full, and instead of doing what it SAID it was going to do, Picasa (yes, 3, the latest version) decided to drop me a friendly warning and then delete the photos off the memory card. Didn’t even crash, just hapily sat there while the realization that two days worth of photos were flushed down the digital crapper.

I just finished Planet Google, and now I’m really having some second thoughts about trusting any more of my information to this company. If a version 3 of one of their products can do this, what am I to expect from the legion of “Beta” products they’re pushing on the world?

100 blogs that will make you smarter

Camera buying guide 2008

I get asked “what camera should I get?” all the time. And it’s worse around the holidays. First the answer in a nutshell. If you’re rich and want the best, but don’t want to fiddle doing years of research, and trial and error, get a Nikon D700. If you’re on a serious budget but still want a serious camera, get a Nikon D40. If you’re really on a shoestring budget, get a Canon A590. Before we delve into some details, three points to keep in mind:

- Pentax, Olympus, Panasonic/Leica, and even Sony make some interesting, and sometimes very good, products. But Canon and Nikon stuff has fewer weird quirks and ugly surprises, and more options for expansion.

- Megapixels don’t matter anymore. The difference between 6 and 12 is actually sort of small, and for the kind of prints you’ll be making any camera you can buy today has enough resolution. The exception is for artists*.

- Three things you need to pay attention to if you’re a novice using your new camera: ISO, Flash (just leave it OFF most of the time), and exposure compensation.

Pocket cameras

The current shining star of small, inexpensive cameras is the Canon SD880 IS, currently selling for around $250 (it’s brand new — the price will come down over the next few months). All the Canon compacts are great, but this one, an update of my beloved SD870, has a wide-angle lens and a big display. If you want even cheaper, Canon makes a zillion ever-shifting models in the SD and A series, of which the current cheapest is the aforementioned A590, which currently sells for around $115. The picture quality is the same; the difference is that the A series is bigger, doesn’t come with rechargeable batteries, and is missing some of the extra bells and whistles. (This strikes me as a great camera for kids.) For some reason, Nikon compact cameras haven’t been worth very much for the last few years.

Cheap SLRs

The larger sensor on SLRs allows them to take pictures that are much much better then any compact, especially in low light. They also don’t have any shutter lag, and are more fun to use. If you enjoy taking pictures, you probably want one of these. Good news is that the Nikon D40 has been around for awhile, and you can find them for just over $400 sometimes, which is sort of amazing considering SLRs average around a thousand bucks. The downside is that there’ll probably be a new version of this camera soon with a bunch of spiffy new features, and more megapixels. On the other hand, it’ll cost hundreds of dollars more, and trust me, those features are silly. Canon has a line of inexpensive SLRs, too, and they’re worth looking at. For most people, though, the Nikon will be easier to use. (The one big issue with Nikon SLRs is lens compatibility. If you think you might want to start collecting and switching lenses, the D40 will cause you grief.)

The Camera-for-Life

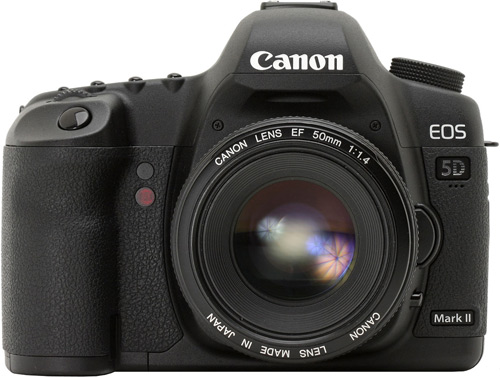

Just in the last six months, two interesting cameras have come out that are interesting because they arguably have “everything you’ll ever need” in a digital camera: the Nikon D700 and the Canon 5D Mark II. These cameras have three things that make them exceptional: (1) full frame sensors, meaning that old lenses are compatible, and work the same way they did on film cameras, (2) Big and high-resolution displays, and (3) lots of megapixels. They’re made out of solid metal, take fantastic photos in very low light, and are a pleasure to use and hold. They’re also big, heavy, and very expensive. Do what you will, but I’m saving up for the new 5D (it’s actually not even out yet).

Conclusion

The bad news is that every single model that exists has something kind of important going against it. The good news is that digital cameras have been around long enough that they’ve been refined to the point where they’re all pretty great. Let your instincts guide you, and you’re probably not going to make a bad choice. (One funny thing about the three pictures above: not to scale! The first camera is actually smaller then it looks in the photo, the middle one is about right, and the 5Dii is much much bigger. Seriously, if someone tries to take it, you can use it to clock them upside the head.)

One last note, about movie modes: the compact cameras all have a movie mode, and most SLRs do not. The two exceptions are the Canon 5D Mark II, and the not-yet-mentioned Nikon D90.

Update: Ken Rockwell’s rave review of the Canon SD880.

* If you’re most people, you’ll be looking at your pictures on the screen and ordering 5×7” or 8×10” prints, for which 6 to 12 megapixels is great. You can actually order nice 13×19” prints from these cameras, too — I’ve used to make 11×14” prints from 3 megapixel images, and they looked fine. Of course if you’re an artist, you want to be able to print big, and in this case a digital camera is not going to be much more then a toy for you. You need a medium or large format film camera.

What the hell are we going to do about the idiot auto industry?

The American auto industry deserves to die so richly it makes me sputter. It’s pretty well exemplified by Bob Lutz, G.M.’s vice chairman, who’s been infamously quoted as saying, “…global warming is a total crock of shit. … Hybrids like the Prius make no economic sense.” It’s been just like with the housing bubble and the Iraq war, where a chorus of reasonable voices called out for the obvious correct action for years. Except that with the auto industry, we’ve been telling them for decades. Please build us better cars. Please not with the upsized SUVs. Oh, and, who killed the electric car again?

Thomas Friedman was watching TV in September:

They were interviewing Bob Nardelli, the C.E.O. of Chrysler, and he was explaining why the auto industry, at that time, needed $25 billion in loan guarantees. It wasn’t a bailout, he said. It was a way to enable the car companies to retool for innovation. I could not help but shout back at the TV screen: “We have to subsidize Detroit so that it will innovate? What business were you people in other than innovation?” If we give you another $25 billion, will you also do accounting?

So, yeah, this is sure as hell an industry that does not deserve to be encouraged. Steve says let ‘em die. But Friedman is more cautious. He quotes the Wall Street Journal’s Paul Ingrassia, who wrote:

In return for any direct government aid, the board and the management [of GM, and any other U.S. automaker accepting a bailout] should go. Shareholders should lose their paltry remaining equity. And a government-appointed receiver — someone hard-nosed and nonpolitical — should have broad power to revamp GM with a viable business plan and return it to a private operation as soon as possible.

That will mean tearing up existing contracts with unions, dealers and suppliers, closing some operations and selling others, and downsizing the company. After all that, the company can float new shares, with taxpayers getting some of the benefits.

But you see where this starts to lead. Back to Friedman:

I would add other conditions: Any car company that gets taxpayer money must demonstrate a plan for transforming every vehicle in its fleet to a hybrid-electric engine with flex-fuel capability, so its entire fleet can also run on next generation cellulosic ethanol.

Of course others have plenty of more drastic ideas, and those strict minimum-mileage requirements we’ve been talking about for years are just the tip of the iceberg. But you see it’s not as easy as “fix it and then make them run it better.” You can solve problems with banking with more regulation, because “innovation” in the banking industry is generally considered the source of trouble. In the auto industry, innovation is the way out, and you cannot use legislation to force innovation. Just doesn’t work. Might work for a few months or a year, but eventually you’ll be forcing the wrong kind of innovation, and digging yourself a deeper bailout hole for next time. Friedman even acknowledges this — sort of — by jokingly suggesting putting Steve Jobs in charge of GM for a year.

No my friends. The American auto industry has had ample opportunity to fix itself. Instead it has chosen to cruise on easy Lincoln Navigator profits (“take a Ford Expedition, add some sound insulation, raise the price by $10,000, and hold your breath”) and a powerful Michigan legislative delegation. It fought safety standards, it fought milage standards, and it churned out the same crap, clad in differently styled plastic, for decades. The legion of workers it employs are the only plausible argument for saving it, but ultimately you’d be doing them no favors. Bailing out an industry and then regulating it to “improve” really is straight Socialism. And even if Republicans are right that this is the time to throw everything they’ve ever stood for out the window, the problem remains that Socialism does not work. Good money after bad. Delaying the inevitable.

Sorry, but I’m with Steve on this one. These companies have been bailed out before. They’ve been warned. They had plenty of opportunity to fix their shit when they were flying high on those 100% SUV profits. And they staunchly refused. They need to survive on their own or die this time.

Lost formats archive

The Lost formats archive. Sort of more interesting for the design then the content. It’s cool they included Sony Memory Stick, though.

Change.gov

The Barack Obama Twitter account appears to have packed it in, and I think that’s as it should be. The campaign is over, and it would be a mistake to link Obama’s campaign marketing efforts too much with his presidency. Adam Lisagor wondered if Obama would continue to use his logo, and it would appear that he will not.

The Barack Obama Twitter account appears to have packed it in, and I think that’s as it should be. The campaign is over, and it would be a mistake to link Obama’s campaign marketing efforts too much with his presidency. Adam Lisagor wondered if Obama would continue to use his logo, and it would appear that he will not.

This, on the other hand, is more like it: Change.gov, a brand new site designed by Obama’s people as only they could, and bringing a completely fresh approach to how the government uses the internet to interact with the people. It’s a little light right now, but it has lots of potential. I would like to see the “share your story/share your vision” features turn into something more like an internet forum, where the stories can be shared and discussed.

And I’d like at least a little of that radical transparency brought in: What newspaper articles and editorials did Obama find provoking today? Who’s he meeting with today? What’s being talked about inside the White House today?

I don’t think we’re ready for, “fire the publicist / go off message / let all your employees blab and blog,” in the White House, but we would benefit from whatever baby steps Obama can take in that direction, and Change.gov seems like just such a step.

Every Block launches in Miami

30 Rock S03E01 on Hulu

30 Rock S03E01 on Hulu, a full week before the on-air broadcast. I take back whatever smack I may have talked about Hulu in the past. This is the future of TV.